Nigeria’s $2 Billion Climate Fund: A Critical Examination of its Role in Energy Transition and Bioeconomy Paradigms

Nigeria's $2B climate fund aims to accelerate energy transition, but faces technical, economic, and systemic challenges.

Nigeria, a nation grappling with the dual challenges of energy poverty and climate change, has recently unveiled a significant commitment to its energy transition agenda: a $2 billion National Climate Change Fund. Announced at the Abu Dhabi Sustainability Week summit, this initiative, alongside the Nigeria Climate Investment Platform aiming for an additional $500 million, signals a strategic pivot towards green finance to drive decarbonization efforts [1]. This development represents a critical juncture for Nigeria’s bioeconomy, potentially altering its foundational paradigms by fostering investments in renewable energy, methane abatement, and green industrialization. However, a rigorous examination reveals inherent technical complexities, scalability hurdles, and economic trade-offs that warrant careful consideration.

Mechanism and Evidence: Decarbonization Pathways and Technical Underpinnings

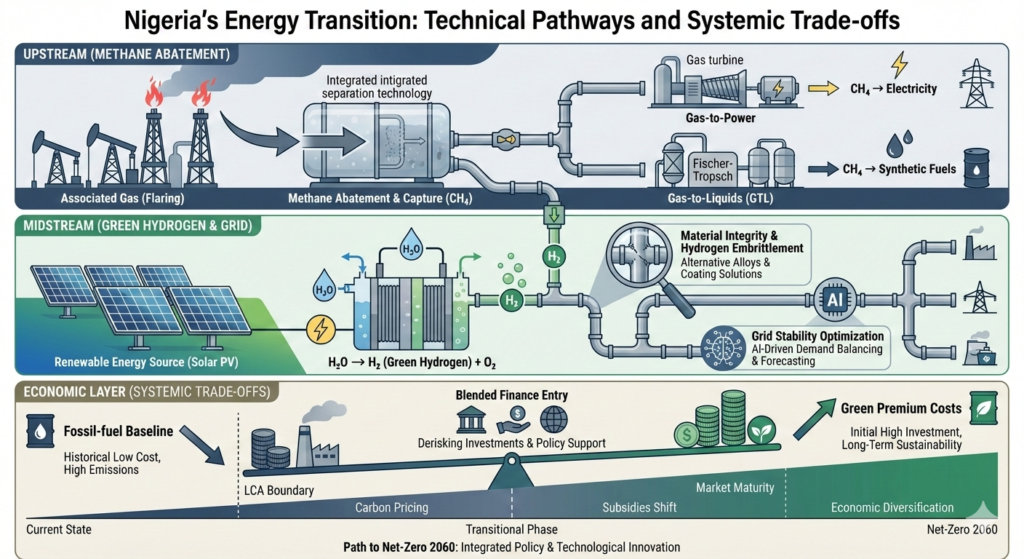

The core of Nigeria’s Energy Transition Plan (ETP), targeting net-zero emissions by 2060, hinges on several key decarbonization pathways. A primary focus is the reduction of methane emissions, particularly from gas flaring, a pervasive issue in Nigeria’s oil and gas sector. While the ETP aims for a 100% reduction in methane from flaring by 2030, recent data indicates that approximately 7.2 billion cubic meters of associated gas were flared in 2023, highlighting a persistent challenge [2]. The technical mechanism for methane abatement often involves gas utilization projects, converting flared gas into electricity (gas-to-power) or liquid fuels (gas-to-liquids). These processes, while reducing direct methane release, require substantial capital investment and robust infrastructure, including gas gathering networks and processing facilities. The efficiency of these conversions, and their overall lifecycle greenhouse gas (GHG) footprint, must be meticulously assessed through Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to ensure genuine environmental benefits.

Another critical component is the exploration of green hydrogen. While current hydrogen production predominantly relies on Steam Methane Reforming (SMR), a process with significant carbon emissions, Nigeria’s ETP is investigating electrolysis powered by renewable energy for green hydrogen production [3]. This shift involves complex electrochemical processes where water is split into hydrogen and oxygen. The scalability of this technology is directly tied to the availability of abundant, low-cost renewable electricity and water resources. Furthermore, the existing gas infrastructure, while potentially repurposable for hydrogen transport, faces technical challenges such as hydrogen embrittlement in pipelines, necessitating material upgrades and specialized compression technologies. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) for grid modernization and efficiency is also prioritized, aiming to enhance stability and reduce transmission losses in a historically unreliable power grid.

Critical Perspective and Barriers: Scalability, Economics, and Systemic Trade-offs

Despite the ambitious financial commitments, the path to a sustainable energy transition in Nigeria is fraught with significant barriers. The sheer scale of the $2 billion fund, while substantial, pales in comparison to the estimated $25-30 billion annually required for climate finance [1]. This funding gap underscores a fundamental economic challenge: the prevalence of a “Green Premium.” This term refers to the additional cost of choosing a clean technology over its fossil-fuel-based alternative. For Nigeria, a developing economy, this premium can be a significant deterrent, impacting the economic viability and adoption rate of cleaner technologies. The oversubscription of green bonds, while indicative of investor appetite, represents a fraction of the required capital, suggesting that traditional market mechanisms alone may be insufficient to bridge the financing gap [1].

Regulatory and technical barriers also impede large-scale adoption. The existing regulatory framework, often designed for a fossil-fuel-centric economy, may not adequately incentivize or facilitate the deployment of nascent green technologies. For instance, while the Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA) launched a $500 million Distributed Renewable Energy Fund, the integration of these decentralized solutions into a centralized, often unstable, national grid presents operational and regulatory complexities [1]. Furthermore, the transition from fossil-fuel-based economic development to a low-carbon model involves complex trade-offs, particularly for a nation heavily reliant on oil and gas revenues. Balancing these economic imperatives with environmental sustainability requires a nuanced policy approach that addresses both the immediate needs for energy access and the long-term goals of decarbonization.

Strategic Implications and Future Research: Navigating a Complex Transition

Nigeria’s commitment to a $2 billion climate fund, while a positive step, underscores the immense strategic implications for its energy sector and broader bioeconomy. The emphasis on blended finance, combining public and philanthropic capital with private investment, is a pragmatic recognition of the need to de-risk green projects and attract diverse funding sources [1]. This approach is crucial for emerging economies where sovereign guarantees for large-scale projects may be unsustainable due to existing debt profiles. The development of a Climate and Green Industrialisation Investment Playbook is also a vital step towards providing clarity and guidance for private investors navigating the complex manufacturing policy and regulatory landscape.

However, significant research gaps remain. Future research should focus on developing robust LCA methodologies specifically tailored to Nigeria’s unique energy mix and industrial processes, allowing for a more accurate assessment of the true environmental benefits of proposed projects. Furthermore, in-depth techno-economic analyses are needed to quantify the “Green Premium” for various renewable energy and bioeconomy technologies in the Nigerian context, identifying specific policy interventions that could mitigate these costs. Research into innovative business models for distributed renewable energy, particularly those that leverage local resources and foster community engagement, is also crucial for achieving universal energy access alongside decarbonization. Finally, exploring the socio-economic impacts of transitioning away from fossil fuels, including job creation in green sectors and retraining programs for displaced workers, will be essential for a just and equitable energy transition. Nigeria’s journey towards a sustainable bioeconomy, propelled by strategic investments and critical analysis, offers a compelling case study for other developing nations navigating similar complex transitions.